“But what I am …”

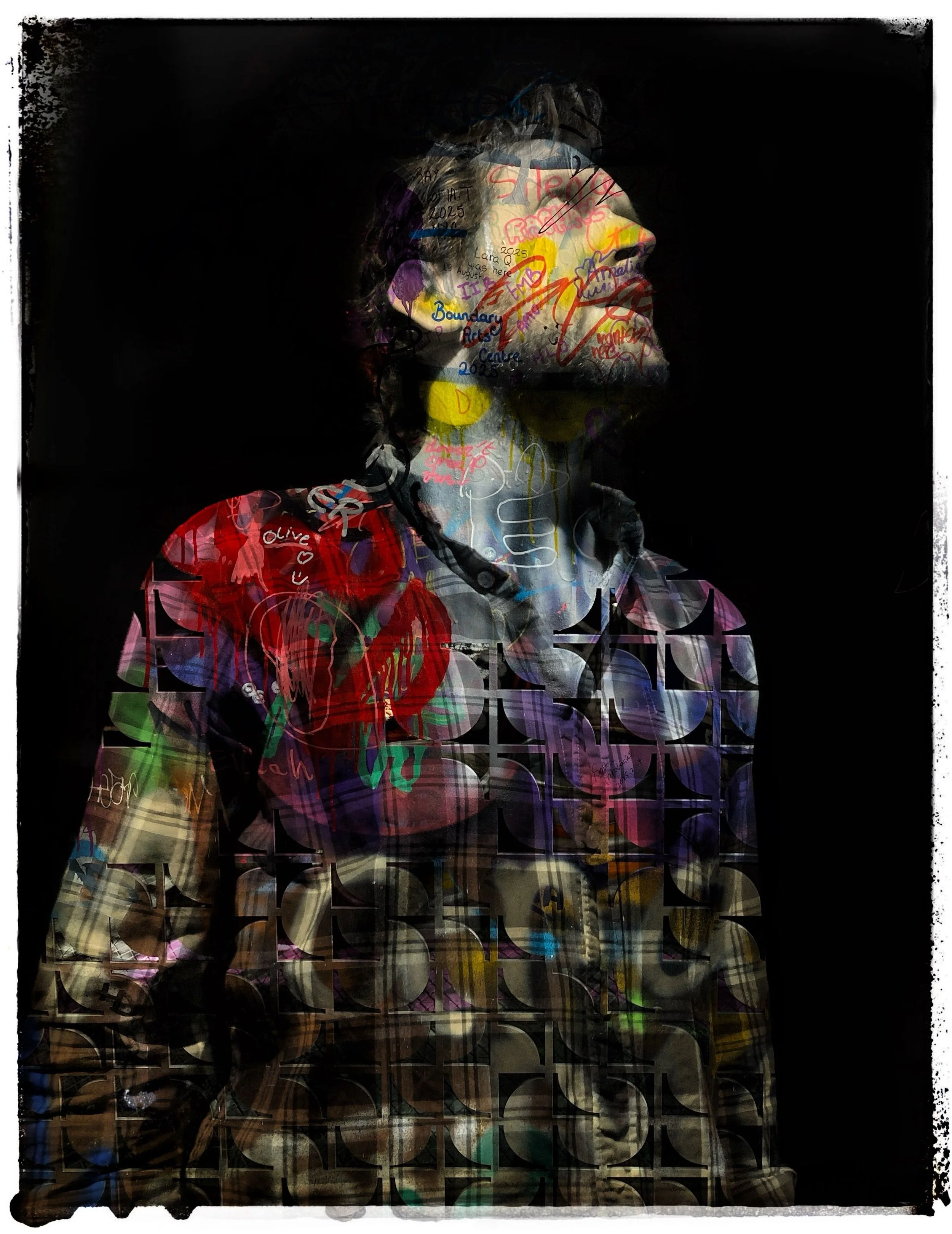

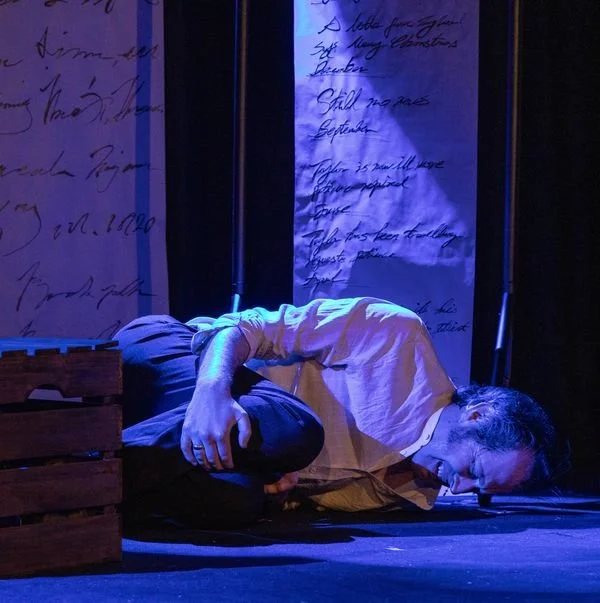

Step inside the asylum room of 19th century “peasant poet” John Clare as he moves restlessly between joy and existential despair.

Confined, but desperate to be free again, Clare’s art becomes his refuge and rebellion.

The walls of his cell dissolve and Clare’s memories, delusions and visionary imagination collide - igniting through song, story and beats.

His inner world bursts outward, revealing the fields and natural world he loved, taverns he frequented and the landscapes of a unique, extraordinary, tormented mind.

Driven amidst the chaos to preserve his identity by completing the work that could secure his voice beyond the asylum walls and for the future, is salvation within his grasp?

CAMDEN FRINGE AUGUST 2025

Photography by Chris Charlton

The show had a tryout over three performances at the Courtyard Theatre, London, directed by Clemmie Reynolds and starring Paul Westwood as John Clare

Check out audience reactions below …

Reviews

***** ….riveting and immersive..a virtuoso performance. The music is a dextrous blend of the folk music Clare would have known and loved, and of our modern, ever more discordant time. The play is witty, agile and illuminating as Clare, from his room, tells his tragic story and shares his poetry in song. A magical hour ….”

Katherine McMahon, Novelist

***** ….lightened by moments of ribald humour…sparkling energy and conviction…the music breathes extra colour and poignancy into the words.

Elaine Guy, Journalist

94% OF THE AUDIENCE OVER THE THREE PERFORMANCES RATED THE SHOW 4* OR 5* FOR OVERALL ENJOYMENT

“The acting is absolutely incredible!”

“Interesting. Captivating.”

“Really enjoyed it. Brilliant actor. The music really added to the drama and emotion.”

Audience Comments

MORE AUDIENCE REACTIONS

John Who?

John Clare (1793-1864) was the son of an agricultural labourer and began work on local farms at the age of seven, though he’d had a basic education up to that point. He began writing his own poetry at home in secret, and whilst out walking in the fields surrounding his Northamptonshire village, Helpston. He was hugely inspired by the natural world where he felt at peace, and the Enclosures Act, which fenced off previously common land, caused him deep unhappiness because he could no longer roam freely in the fields and hedgerows he loved so much and knew so well.

He played the violin and collected and wrote folk tunes and songs. He was a regular at his local, The Bluebell Inn, enjoyed regular nights out with ‘the boys’ and had a lively interest in the young women of the village!

In 1820 his first book, Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery, was published and created a a bit of a stir. Clare visited London, where he enjoyed a brief period of celebrity in fashionable circles. He made some lasting friends, among them Charles Lamb, and admirers raised money to help support him and his family. That same year he married Martha ('“Patty”) Turner, the daughter of a neighbouring farmer: the “Patty of the Vale” of his poems.

From then on he encountered increasing bad luck. His second volume of poems, The Village Minstrel (1821), attracted little attention. His third, The Shepherd’s Calendar; with Village Stories, and Other Poems (1827), though containing better poetry, met with the same fate. His annuity was not enough to support his family of seven children and his dependent father, so he supplemented his income as a field labourer and tenant farmer.

Poverty took its toll on his health. His last book, The Rural Muse (1835), though praised by critics, again sold poorly; the fashion for ‘peasant poets’ had passed.

Clare began to suffer from fears and delusions - at times he seemed to believe he was Lord Byron, Shakespeare and a prize fighter, and he often believed he was married to his first love, Mary Joyce, as well as Patty, his real wife.

In 1837, through the agency of his publisher, he was placed in a private asylum at High Beech, Epping, where he remained for four years. Improved in health and homesick, he escaped in July 1841. He walked the 80 miles back home, penniless, eating grass by the roadside as he had no food and sleeping pointing north so he knew in which direction to walk the next morning. He left a moving account, in prose, of that journey, addressed to his imaginary wife “Mary Clare.”

At the end of 1841 he was certified insane. His admittance notes record ‘addicted to poetical prosing’ as the cause of his confinement, but it is thought he may have suffered from bipolar disorder which was an unknown condition at the time.

He spent the final 23 years of his life in St. Andrew’s Asylum, Northampton, writing some of his best poetry there.

In 1860, four years before he died, he wrote in a letter:

“Dear Sir,

I am in a madhouse and quite forget your name or who you are. You must excuse me for I have nothing to communicate or tell of. And why I am shut up I don’t know. I have nothing to say so I conclude

Yours respectfully,

John Clare”

It appears that neither his wife or any of his children probably ever visited him in his 27 years in the asylum.